Hearty Arty Erte Party.

My entire Erte Article…or should that be …erticle…

When I first became interested in fashion illustration, I think it was sparked by Daphne on Scooby Doo. You know her, the mystery-solving glamour puss cartoon character, animated as a fashion plate. I always liked to draw women and girls in imaginative or outlandish outfits. At university I wrote a thesis about the progression of my childhood drawings as they evolved into fashion illustrations.

Erte was one of my favourite illustrators. He didn’t just draw, he designed costumes as well.

There is something about the simple elements in Erte’s drawings: the clean lines; the perfect balance of patterns; the elegant fingers and the jazzy-jewel colours. The fact that he designed costumes for Mata Hari makes a tenuous connection to Daphne- two fashion loving temptresses leading dangerous lives!

Erte came from a privileged background, born in St Petersburg in 1892. His real name was Romain de Tirtoff, Erte being the phonetic pronunciation of his initials, when said with a French accent. Some might say going with the English pronunciation ArrTee (Arty) might have been more appropriate.

Fortunately for Erte, and the worlds of fashion and theatre, his family did not force him to join the navy as was their usual tradition. Instead they allowed him to study portrait painting at the Academie Julien in Paris from 1912. This choice of art college was a good fit for Erte, being more forward thinking than the traditional Ecole de Beaux Arts. (The EBA hadn’t allowed women to study there until 1897, and women were not allowed to draw nude male life models.)

Within a year Erte had begun to work with Paul Poiret, famous for swathing women in harem pants and elaborate hemlines. This connection lead to his first signed fashion illustrations appearing in Gazette du Bon Ton in 1913. Gazette du Bon Ton was a very new publication at the that time, the centrepiece was its fashion illustrations of which there were 10 colour plates in each edition. As an aside, it was a feature in this magazine, of La Fontaine de Coquillages by George Barbier, which lead to me painting a mural on my bathroom wall. Here it is:

After a lightning fast start to his career, suddenly scarlet fever called a hiatus in 1914. Undeterred, Erte took this as an opportunity to move to Monte Carlo with his cousin Prince Nicholas Ouroussoff, where the air was healthier. In spite of his preposterously wealthy background, Erte couldn’t live on fresh sea air alone, he submitted sketches to Harpers Bazaar in America. Thus began a 22-year association with the magazine, during which time Erte produced 240 covers.

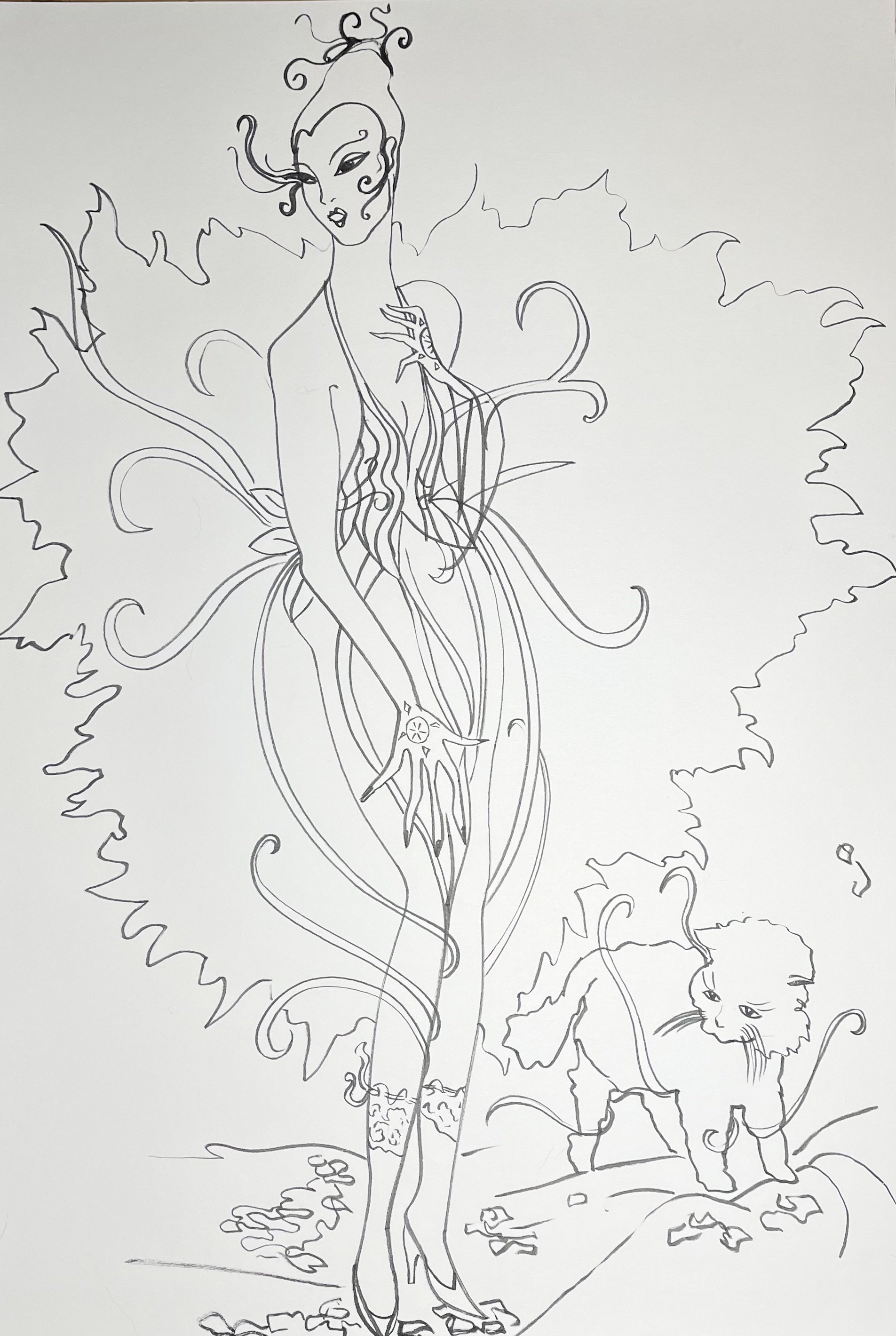

I have been gleefully dabbling in creating my own versions of Erte’s work, and including my cats sometimes because they lend themselves to Art Deco depiction too.

Erte might not have found fame with Harper’s Bazaar had he not first been featured by the relatively short-lived but seismicly important Gazette du Bon Ton. The Gazette was launched at about the same time that Erte arrived in Paris, and it ran until 1915. The Gazette was then relaunched in 1920 and ran until December 1925. I wish it would relaunch again for its 100th anniversary, I could really do with it now. As it is, there are 12 precious volumes published.

An important link between Erte, Gazette du Bon Ton and Harper’s Bazaar is the use of the Pochoir technique which was eagerly embraced. Pochoir was the fashionable medium for showcasing fashionable clothing at the time.

Without diverting too much, the Pochoir technique was perfected in Paris in 1910. It utilised a mixture of stencilling and watercolour which gave a result perfect for creating and replicating fashion illustration and textile prints.

Very unusually for the time, indeed for any time, Erte was offered a ten-year exclusive contract to design covers (and to contribute to features inside) for Harper’s Bazaar. This contract was then extended for another 10 years. The owner, William Randolph Hearst, saw Erte as the magazine’s protoge, declaring, in a 1917 editorial, To glance at an Erte drawing is amusing. To look at one is interesting. To study one is absorbing. That any human being can conceive- and execute- such exquisite detail is positively miraculous.

I wonder what Erte’s family thought of this adoration of their errant child? Even though Erte had willingly become known by his initials, RT, in some way to protect his family from the scandal of his rejection of a naval career in favour of fashion, everyone knew the artist was none other than Romain de Tirtoff. One and the same.

In fact, in 1922, Erte’s chosen career saved his family. He was able to use his high-falutin’ fashion connections to bring his family from Russia to the relative safety of Paris, after the revolution.

I also ask the same question that William Randolph Hearst asks, and to which there is no answer, What would Harper’s Bazaar have been if it wasn’t for Erte?

Erte’s exuberant style, featuri flamboyant women decked with feathers and ornaments contrasting with rigid and angular men framed by geometric architecture defines the Art Deco period. Erte was a prolific creator, a workaholic automaton, as all the legendary artists and designers seemingly are. He was driven by an unquenchable need to create.

Undeterred by two world wars and even the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Erte continued to produce his trademark work. Even the different art movements that he lived through (Cubism, Fauvism, Expressionism etc) did not detract from his Art Deco style.

In my Substack notes, earlier this week, I asked the question: If Erte is known as the Father of Art Deco, who then is the Inventor of Art Deco? The answer came back: A.M. Cassandre. Which is interesting, because A.M. Cassandre was Erte’s replacement at Harper’s Bazaar after Erte’s falling out with new editor Carmel Snow, in 1936.

Did the Father and the Inventor of Art Deco get on with each other? Probably not, but let’s return to something more cheering:

Joy of joys, I have found copies of Gazette du Bon Ton! Not actual ones, but ones I can look through, virtually. If you are similarly obsessed then do visit the Internet Archive where you can flip through an actual edition of 324 pages. Heavenly.

The edition featured is from 1922, when Erte was still ensconced exclusively at Harper’s Bazaar therefore he does not feature here. However, the delights from this year do include a never-before-seen (by me) George Barbier and several Paul Poirets so that’s plenty compensation. I strongly recommend you view this tome at home.

Erte also designed costumes and sets for the Folies Bergere and for Hollywood and Broadway. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Erte’s personal fortune was wiped out and there was less demand, or finance available, for lavish productions. Erte continued to work on smaller scale ballets and opera.

Erte left Harpers Bazaar in 1936. Perhaps he would have stayed on, were it not for his disagreements with new editor Carmel Snow, as mentioned in last week’s blog. The owner of Harper’s Bazaar, William Randolph Hearst, was most scathing about Erte’s replacement, poster artist AM Cassandre, saying “I do not know of anybody who could do worse, unless it be Picasso.” Cassandre is a very interesting character though the industrial style of his work makes him a surprising choice of illustrator for a lifestyle magazine. See more about him and his not-very-fashiony work here.

This begs the question though, if you were the owner of the magazine (and Erte’s number one fan) could you not step in and prevent him leaving? Another question to be begged here is with regard to Picasso- why did Hearst have negative feelings toward Picasso? This is another fascinating story in itself. However, we must put aside all others and return to our hero Erte…

Erte stayed in Paris throughout WW11, leaving only afterwards to pursue work wherever he could. Including Blackpool. In fact, for 20 years, Erte designed shows for the Blackpool Opera House. I didn’t even know that Blackpool had an opera house, but there is only one Blackpool in the whole world so it must be true, and this must be the one. Erte described Blackpool as “ghastly” which seems somewhat ungrateful whilst also somewhat accurate.

Erte continued to produce work in England, including Brighton. He had an affinity with the seaside and much of his work at this time reflects an “under the sea” theme.

1967 was a big year for Erte. Not only was another huge fan of his born (me), but art dealers Eric and Salome Estorick gave Erte his first solo show in New York. His entire collection was then bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Estoricks had founded the Grosvenor Gallery in London in 1960. They also, in 1967 curated an exhibition of Erte’s drawings, including his Alphabet Suite. The exhibition was so successful that a revival of interest in Erte’s work surged. The gallery then restaged the exhibition again in 2017 to celebrate 125 years since Erte’s birth. Again the exhibition was so successful that its run was increased. The drawings exhibited in 2017 are from the personal collection of Eric and Salome Estorick.

Also in 2017, 18 years after Erte’s death, 3 examples of Harper’s and Queen (Harper’s Bazaar) covers designed by Erte were beamed out on to the Empire State Building to celebrate 150 years of the magazine. Erte’s legacy lives on.

I have included a link to the 2017 exhibition here so that you can see all the works.

For the final 22 years of his life, he died in 1989 at the age of 97, Erte continued to be involved in a variety of projects, from designing covers for Playboy magazine to creating labels for bottled water and cognac. If you have not heard of Erte before, I implore you to look him up. He will brighten your day, and make you want to swan around draped in exquisite fabrics and trailing pearls.

Art critic Brian Sewell says of Erte, “ He had neither equal, nor rival; he was, and remains, unique.”