Once upon a Time…

I visited Ethiopia, the land of Origins. And this is how the story of my Art Business started.

By popular demand from visitors to my current exhibition, I am republishing this article here. I originally wrote it in 2017, it was commissioned by the Anglo-Ethiopian Society magazine.

Elizabeth Blunt, who is mentioned in the first line, is a BBC journalist who was based in Addis Ababa. We are both members of the Anglo Ethiopian Society. If your interest is piqued, find out more about the Anglo Ethiopian Society.

How the Women of the Hamer Tribe Changed my Life

by Zoe Akroyd Parker

“The tourists take all these photos and we don’t know what they do with them. Do they laugh at us?” the Hamer tribeswomen asked Elizabeth Blunt.

I was stunned when I heard Elizabeth recount this story, and I also felt quite tearful. I was sitting in the audience, enthralled by her talk, Reporting Ethiopia 2007-2009. It never occurred to me that the Hamer tribeswomen might think that people would laugh at them, because after I met them my whole life changed in a most wonderful way.

I had never considered visiting Ethiopia until one evening in February 2015, when my cousin introduced me to a group of Ethiopian men whom he was working with. They were all working as translators on a documentary for channel 4. It was called The Tribe and it followed the lives of the Hamer Tribe in the Lower Omo Valley. During that evening, which we spent at Lalibela restaurant in Tufnell Park, London, I was mesmerised by the Ethiopian men’s description of life in the tribal villages. I loved their photographs and stories, and by the end of the night I had already made up my mind to go.

Six months later, I flew into Arba Minch where I was happily reunited with one of the translators, Ayeto. We hired a car and a driver and travelled down towards Ayeto’s home town of Turmi. On the way, we stopped off to visit my first tribe, the Arbore, somewhere in the middle of surely the hottest place on earth. We had bumped for miles along a dusty road that looked like the base of a river bed, until we reached the village.

Our driver went off to find us some lunch. I was expecting plastic-wrapped supermarket sandwiches- instead he surprised me with an omelette, which the three of us shared, scooping it directly from a carrier bag with our hands. We ate outside the car, perched on rocks and branches, the sand punctuated with bristling bushes and a few sheep’s skulls. It was the hottest, driest, dustiest place I had ever been.

As we walked towards the village huts, the women and children came out to look at us. Through the heat-haze I could see the blurry shapes of a huddle of men under a tree. These turned out to be the older men, the young men were all out for the day (out where? I wondered). As the women approached, I could hear the clanking of the heavy metal bangles around their thin ankles, their feet shuffling across the sand in sandals made from car tyres. I was expecting to see down-trodden, weather-beaten characters so I was totally unprepared for the women’s cool beauty. I was delighted that they were fascinated by my tattoo, naively I thought that I was the first white person they had ever seen.

The sun glared straight through my sunglasses and I put my hand across my face to shade my eyes. I noticed that the women used only a thin cloth to protect themselves from the heat and light. (Later on, after I had lost my Raybans forever down a long-drop toilet, I remembered how the Arbore Tribe had managed without sunglasses and I decided I could too.)

The Arbore girls shuffled into position, for photographs. They were waiting for me to choose who to photograph, which I felt quite uncomfortable about. There seemed to be a kind of hierarchy, I could tell from their glances and shrugs at each other. I tried to be diplomatic in my selection but I didn’t know how to choose, or if there were any rules. I noticed some of the young women seemed coy or resigned to the tourists, others liked to hog the limelight. Some shrank back beneath the cloth cover, others thrust themselves forward, breasts first. I lined up with the girls for our group photos, some of us awkwardly put our arms around each other.

I noticed their clothes, I asked where their beads came from. Markets, they said. They all wore colourful beaded necklaces from neck to navel, with beaded wristbands and headdresses. Each girl wore the same kind of skirt, made from goatskin with the hair removed, wrapped around in a double-layer and edged with white beads. The animal skins had a papery texture, like peelings from a cardboard box. The girls’ heads, like their animal skin skirts, were also bare, except for a beaded head band, which emphasised their high cheekbones. On each of their fingers they wore rings which encircled their whole knuckle. Their matching earrings were formed by a tight spiral of metal; everyone wore the same style. They stood in a row, elegant as gazelles, and I stood happily with them, in my mass-produced clothes from Sainsbury’s.

As we drove along the road to Turmi, I was delighted to see two Hamer women emerging from the bushes in their instantly recognisable tribal attire. As I had watched The Tribe on TV I had wondered if the women were dressing up for the cameras and I was so pleased to see that they dressed this way all the time. I was scared to take their photograph so I passed the camera to Ayeto and he took a picture while I passed some screwed-up Birr into the women’s outstretched hands.

As we continued into Turmi we saw more and more Hamer women. I preferred to see them going about their business naturally rather than posing for tourists’ photographs. I was fascinated by the clothes they wore and the way they wore them; I wondered how the fashion rules for each tribe had evolved and how much variety was allowed.

As the weather in Turmi is slightly cooler than the Arbore village, the women are comfortable wearing more clothes. Their outfits are made of two pieces of goatskin- a chest piece and a skirt, with the goat’s hair intact. Strings of red and yellow beads are carefully stitched into the hides and rows of cowrie shells are added around the neckline. The Hamer women also wear wide, beaded belts in red and black and festoon their arms with beaded bracelets and metal rings. At the rear, their beaded skirts sweep almost to the ground, following their bodies as they move along, like crocodiles’ tails.

Just prior to my visit I had visited the fashion designer Alexander McQueen’s Savage Beauty exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. I saw work from his Africa-inspired collection, It’s a Jungle Out There, in which he mixed pony-skin cloaks with impala horns and crocodile heads, as well as blending beaded bodices with horsehair skirts. It was clear to see the parallels that McQueen had drawn from African style, but also funny to see how much effort had been expended to get a “natural” fit. McQueen had cut up the leather to make it fit the human body beautifully, and the Hamer tribeswomen had achieved the same effect by using the whole skin just as it is and waiting for it to soften to their shape over time.

Western women work hard to achieve the kind of coolness that comes so naturally to these tribeswomen, who use only the sustainable materials they have at hand. I laughed when I saw tribeswomen (and men) in the marketplaces accessorising their outfits with pen tops, watch straps and hair-grips dropped by tourists. The tribes wear their clothes so stylishly, to me they look like models – helped by the fact that they have a generally healthy diet and a physical lifestyle.

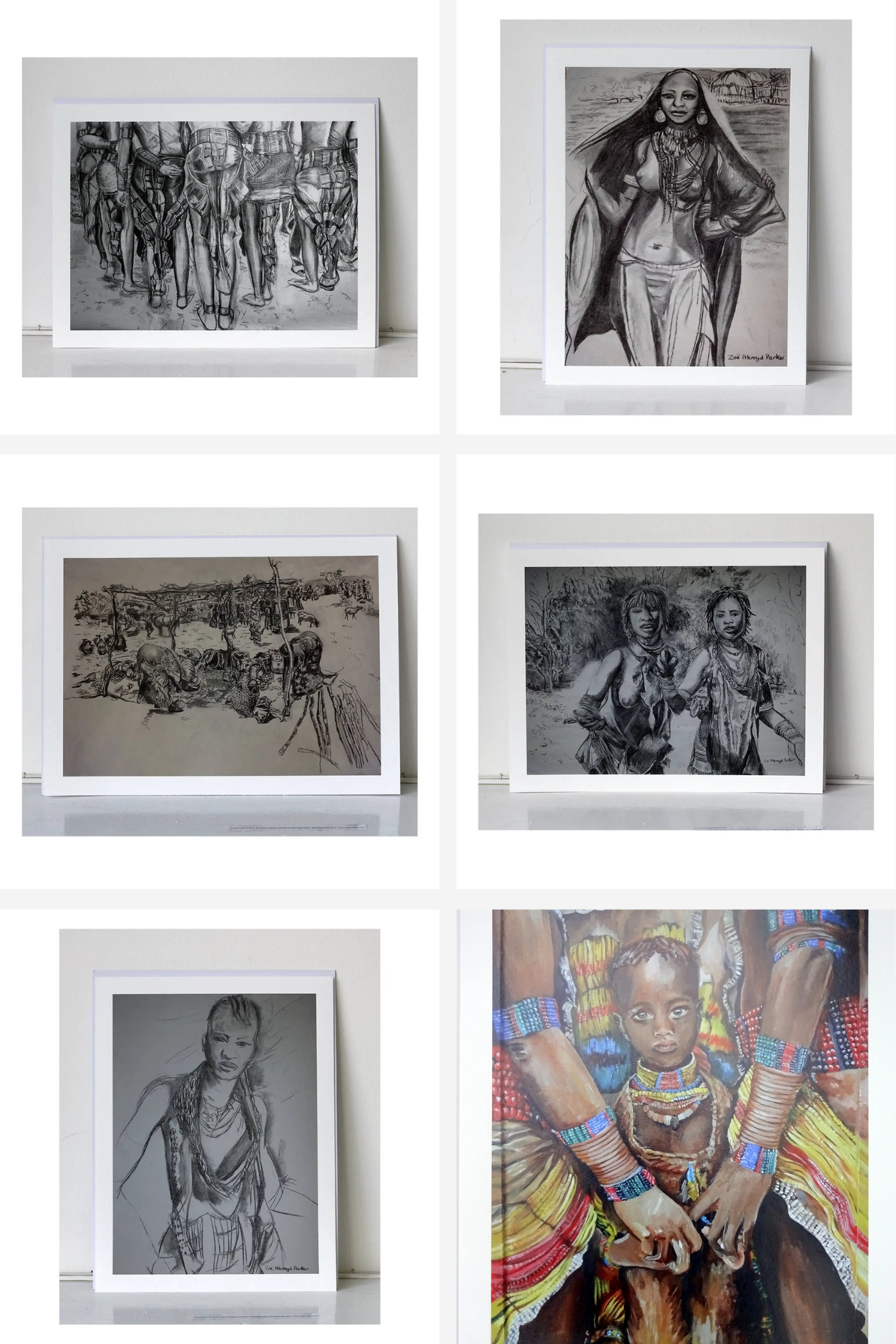

When I returned home to the UK, I began to draw the tribeswomen, using charcoal on newsprint paper. I wanted to use the most basic materials as if I were still in Africa and that is all that was available. Charcoal gave me the freedom to create expressive lines and to add detail and texture. I drew on newsprint because it held the charcoal marks easily and allowed for smudging.

I started off by drawing from my photos of the Hamer women at the Whipping Ceremony, because in my memory they held the most power. At first I had been horrified by the prospect of watching women being whipped by men, but there was something compelling about the whole event, as if the women were in control. I watched as the women competed against each other for the attention of the whipper; how they goaded the men into whipping them. They were also vying for the tourists’ attention. Their outfits were accessorised with heavy, noisy bells around their knees and they held loud trumpets to their lips.

I began to draw the women as they were, standing around in groups- I wanted to show that even though they are all wearing the same clothes, they all wear them in a different way. Next, I drew the women who stood out for me for one reason in particular; such as the one girl standing slightly away from the main group. These are the women that I like to make my subjects, the women who look like the cool girl at the disco. At first it was the attitude, the shape of the women that called me to draw them. Then I moved on to look at the details of their clothes, so that what had begun as a quick fashion sketch I could now embellish with more details to get a proper sense of what they were wearing, and the individual details. By drawing in greater detail it helped me to understand how the garments were created. This gave me a greater connection to the women.

At first I created the drawings for my own pleasure, I showed them to some of my students at the school I teach at, and to a couple of my friends. By the end of 2015 I had created quite a large collection of drawings, and my New Year’s Resolution for 2016 was to host an exhibition. At the time, a friend of mine was the proprietor of The Goldsmith Pub and Dining Room in London Bridge. She kindly agreed that I could exhibit my work there in June 2016. The exhibition was amazingly successful and I was delighted to sell a couple of my original drawings as well as quite a few prints and bags.

I continued drawing and looking for opportunities to exhibit my work, I seized every chance I could and ended up with work in exhibitions almost constantly after that first show.

I returned to Ethiopia with my 9-year old son, Lucas, in the summer of 2016 and we both felt inspired to draw for a great deal of our time there. Lucas enjoyed drawing the animals, birds and huts, I enjoyed looking at the shapes and colours of the buildings and the people. We also returned to watch the Whipping Ceremony- this time it was too packed with tourists for me to comfortably take photos so instead I created some quick sketches from life.

When we returned to the UK, Lucas and I held a joint exhibition of our work in a local gallery. We had added some lino prints, watercolours and acrylic paintings to our collection of work. Following on from this, a high-point for me was that one of my watercolour paintings, “Little House, Big Banana Leaves” was selected by the Royal Watercolour Society for the Contemporary Watercolour Competition and exhibited at Bankside Gallery during March 2017. I had painted the colourful little shack, nestled amongst huge banana leaves, after driving up from the Lower Omo Valley to Addis Ababa.

At the start of this year, I visited Addis Ababa again and showed some of my drawings to a few gallery owners there. To my delight, I was invited to exhibit at Dinq Art Gallery later in the year. I am planning to exhibit along with 2 other artists who have links to Britain and East Africa, Edy Mpisaunga and Evans Mbugua.

Since the start of 2017 I have been invited to host workshops and live-art demonstrations at local galleries, using my charcoal drawing and lino printing techniques. I always talk about my influences and use my Ethiopian images as references. In my classes, we talk about what the tribeswomen might be doing right now, while we are back in the UK drawing them from photographs.

I now plan to make a career for myself as a full-time artist, which all started from my trip to Ethiopia, The Land of Origins. My photos of the Hamer tribeswomen, which I originally took just for the record, became so much more than that. One day I would love to return to the Lower Omo Valley, but without my camera- just to sit and draw the tribes. If the women ask me why I’m not taking photos, I will happily tell them my story.

I hope you enjoyed reading about my experience in Ethiopia, let me know if you have ever been so inspired by a trip abroad that it changed the direction of your life.